Welcome back!

After a bit of an interlude, the blog is back, ready to delve into the murky and fascinating world of epidemics, told through the words of poets and writers. Just when you think that the world of microbes has caused enough destruction to leave little to the imagination, here comes a particularly dark little story of a fictional disease, as told by the master of horror, Edgar Allan Poe…

Oscar Halling’s portrait of Edgar Allan Poe, late 1860s. Image in public domain at Wikimedia Commons [link]

‘The Masque of the Red Death’ narrates the grisly events that occur during the fictional reign of Prince Prospero. The story plunges us straight into a vivid description of the Red Death, a longstanding epidemic with high fatality rates and a gruesome effect on its victims, causing profuse bleeding, pain, seizures – and a mercifully rapid death.

“Blood was its Avatar and its seal”. The death toll is staggering: half the population have already succumbed by the beginning of Poe’s story.

Prince Prospero, who appears indifferent to the plight of his subjects, decides to “bid defiance to the contagion”, and with ample provisions, shuts himself and a thousand friends away in one of his sumptuous abbeys, to dance and merry-make in security from the Red Death. This seclusion continues successfully for the next six months, whilst those without fare poorly.

A motley collection of masked guests, as illustrated by Arthur Rackham in “Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination (1935). Image in public domain at Wikimedia Commons [link]

A masquerade! Prince Prospero certainly knows how to entertain, and throws an extravagant masked ball for his guests. The rooms are decorated vividly, as we enter a realm of metaphors. With some bizarre interior design, Prospero makes his tapestries and Gothic windows colour-coordinate; six rooms in blue, purple, green, orange, white and violet; a seventh of deep scarlet windows and black velvet walls, illuminated with fire. Ominous and wild, the revellers shy away from entering this last room: but each hour, stand transfixed in horror by the disconcerting toll of a pendulum clock from deep within the seventh chamber.

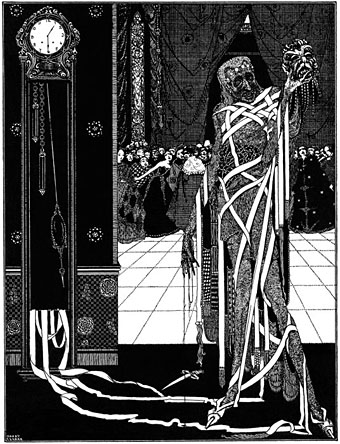

At the twelfth hour, as the clock chimes heavily and the waltzing falters, a masked figure fades into notice; a masked figure of unparalleled distaste, costumed as the Red Death itself. Tall, gaunt, corpse-like, phantasmagorical, daubed with blood, “besprinkled with the scarlet horror”: a vision of nightmare indeed!

“The dagger dropped gleaming upon the sable carpet” by Harry Clarke (1919). Image in public domain at Wikimedia Commons [link]

The encounter, suffice to say, with all its foreboding, ends badly, and rapidly, for Prince Prospero and his courtiers, who believed themselves safe against the Red Death. “One by one dropped the revellers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel, and died each in the despairing posture of his fall… And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

Well! Edgar Allen Poe isn’t renowned for his happy endings, so this gruesome end is probably to be expected. Just as well this is only a fictional disease….or is it?

In the wake of the recent devastating Ebola pandemics of Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea-Bissau, the parallels of the Red Death with one of the known haemorrhagic fevers can’t help but spring to mind. These haemorrhagic fevers include Ebola and Marburg fever, and have similar symptoms of fever, muscle pain, headache, nausea, then diarrhoea, vomiting and in some cases significant bleeding (WHO 2014).

As I suspected, I’m not the first to notice this: in fact, a published article in the journal ‘Emerging Infectious Diseases’ by Vora & Ramanan in 2002 explored this very question! The article is well worth a read and is available here. The authors postulate the mode of transmission of the Red Death (person-to-person, and possible aerosol inhalation) and the potential for either a very long incubation period for the Red Death microbe, or a new exposure to the abbey by an unspecified route.

So could Poe have modelled the Red Death after a known disease, or did he imagine up all of the gruesome features of the whole epidemic? Well, Poe probably have reasonable knowledge of yellow fever, a different type of haemorrhagic fever, – but one which causes liver failure and jaundice, neither of which are evident with the Red Death. Poe was also well aware of tuberculosis, which can manifest with coughing up blood from the lungs: both his mother and wife died of the disease. Since Ebola, Marbug virus and another counterpart, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic virus, all emerged in the 1900s, after Poe’s death, the parallel with the Red Death must be purely coincidental.

Whatever Poe’s experience of contemporary diseases, however, his description of the Red Death is vivid, realistic, and perhaps a warning of how complacency and seclusion in the interests of self-preservation are no match for a virulent pestilence with no respect for social contexts and hierarchy! Perhaps then, we should interpret Poe’s tale as a graphic and timely warning – public health initiatives, take note!

References:

Vora, S.K. & Ramanan, S.V. (2002) Ebola-Poe: A Modern-Day Parallel of the Red Death? CDC Emerging Infectious Diseases 8(12):December 2002

World Health Organisation (2014) Ebola Virus Disease: background and summary. Published 3 April 2014, available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2014_04_ebola/en/

![IMG-20170618-WA0003[1]](https://infectiousreads.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/img-20170618-wa00031.jpg?w=332&h=590)