What would you do if your true passion left a trail of death and destruction behind?

You may have heard of Typhoid Mary, whose love of cooking did just that…

I found this gem of a book in a little second hand bookshop in Glasgow a couple of years ago: J.F. Federspiel’s reimagining of the life of Mary Mallon in ‘The Ballad of Typhoid Mary’. What a nickname to be remembered by! – but unfortunately for Mary and all of her unintentional victims, a very accurate one.

Federspiel, with a bit of poetic license, introduces us to Mary, or Maria Caduff as he imagines her to be, a young Swiss immigrant on the ‘Leibnitz’ ship which docks at New York in 1868, bringing a spectacle of horrors with it as 108 of its 544 immigrants have succumbed to an epidemic. “Plague on board!” holler the newsboys, as Maria is taken in by Dr Dorfheimer, and starts to cook and clean for him. Unbeknownst to Dorfheimer, and to Maria herself at this time, she carries the deadly illness which decimated the Leibnitz passengers, but is herself immune.

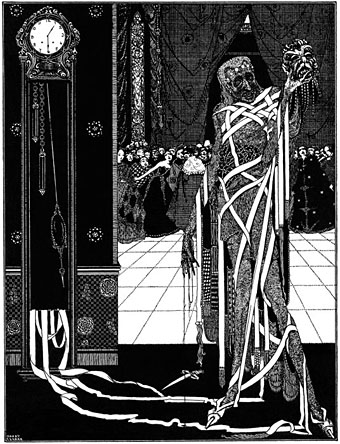

This extraordinary story chronicles Maria’s life as she adopts a new identity of an Irish immigrant, Mary Mallon, travels through various jobs in New York “like an angel of death”, doing the thing she loves most of all – cooking – and almost invariably passing on the infectious germs of Salmonella typhi, or typhoid fever, whilst doing so. Even to her contemporaries, the legend of Typhoid Mary becomes one of nightmares. “Typhoid Mary … a grim-looking cook with gnashing teeth and saliva dripping from her mouth into a steaming, poison-green cauldron.” How uncomplimentary!

Federspiel’s story jumps between a narrative of Mary’s life, and the soliloquy of the paediatrician Dr Howard Rageet presumably writing a biography of Mary in the 1980s. Although this feels to me to be a clumsy method of storytelling, this approach does allow Federspiel to comment retrospectively on the medical facts around typhoid, as well as his semi-fictional historical narrative, so it does add useful perspective to the story.

Lorem Ipsum (2016) Mallon-Mary 01.jpg at Wikimedia Commons

How accurate are the depictions of typhoid? Kudos to Federspiel, he’s done his homework and his descriptions are pretty spot on! Almost without fail, all of Mary’s victims fall ill within 1 to 3 weeks of her arrival into their service, and they tend to suffer from the typical symptoms of typhoid including a high fever, nausea, delirium and voluminous diarrhoea. The death rates are fairly high, up around 10-20% as would have been expected in the pre-antibiotic days. Dr Rageet notes the transmission of typhoid is water and faeces-borne.

All good things must come to an end….before too long the public health authorities get wind of Mary’s accidental secret ingredient, arrest her and isolate her in prison. They prove she is a typhoid carrier, someone who carries the bacterium without themselves becoming sick, but who can pass this on to susceptible people, by finding the typhoid bacteria in samples of her urine and faeces – as per Mary’s medical report below.

Jtamad (2015) MaryMallon.stoolreport.1907.png available at Wikimedia Commons

After much legal uproar, Mary is finally freed and agrees not to cook for anyone else. She doesn’t stick to this promise, unfortunately, and causes an outbreak in a large women’s hospital which gets her noticed again, and this time she is isolated until her death from complications of a stroke more than twenty years later. Poor old Mary!

All in all, this is an intriguing and enjoyable little read which chronicles a fascinating era in history, at a time just before the advent of antibiotics which would have dramatically changed the outcome. Makes me glad to live in a time where health and safety is now known to be so crucial in preventing disease transmission, and where the Typhoid Marys of today can receive treatment to ensure they don’t spread the disease!

Have you heard of Typhoid Mary, or even experienced typhoid yourself! Share your comments and send your questions to Infectious Reads!

![IMG-20170702-WA0012[1]](https://infectiousreads.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/img-20170702-wa00121.jpg?w=270&h=480)

![IMG-20170618-WA0003[1]](https://infectiousreads.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/img-20170618-wa00031.jpg?w=332&h=590)